Traditional Bathhouses of the Eastern Mediterranean: The Forgotten Cultural Architectural Heritage

Although today they are nearly absent from public consciousness or have been transformed into abandoned tourist attractions or luxury restaurants, these structures were once a fundamental element of Islamic urbanism, blending function and engineering, health and spirit, rituals and economy.

Arch. chaam Alkhani

7/27/202510 min read

In the corners of ancient cities across the Eastern Mediterranean, there are buildings that passersby might overlook without realizing they were once the vibrant heart of social, health, and spiritual life. Traditional bathhouses, which formed an essential part of the Islamic urban fabric, were an advanced extension of the Roman and Byzantine legacy in water management and public health.

They were more than just bathing facilities; they were spaces where collective memory was etched, daily life details pulsated, and social relationships, purity rituals, and beauty traditions were shaped—transcending the architectural concept. While their exteriors may seem similar, the intelligent architectural solutions, deep environmental understanding, and intricate social organization they conceal make them one of the most profound manifestations of functional and aesthetic architecture. Behind this sensory beauty lies a design genius built on a complex system of heat, humidity, sound, and light. It’s not just a building… but an integrated system combining technology and meaning.

Although today they are nearly absent from public consciousness or have been transformed into abandoned tourist attractions or luxury restaurants, these structures were once a fundamental element of Islamic urbanism, blending function and engineering, health and spirit, rituals and economy.

But why did these structures disappear so quickly? And can they be reimagined today?

In this article, we explore how bathhouses in Eastern Mediterranean cities were designed, the architectural and cultural differences between them, and what makes them a heritage worthy of attention—and perhaps… revival. We’ll also examine how a deep understanding of these structures could open the door to reviving them with new functions befitting a contemporary world rediscovering “health wellness.”

The Historical Emergence and Evolution of the Architectural Model

The traditional bathhouse in the Eastern Mediterranean represents a significant evolution and qualitative leap from the Roman thermae, which were inherited by the Byzantine Empire and later adopted by Islamic architecture. Islamic architecture added new social, religious, and functional elements to these bathhouses.

The earliest models of Islamic bathhouses appeared during the Umayyad era, notably in palaces like Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi (728 CE) and Qusayr ‘Amra. During the Abbasid period, heating and water systems advanced, while the Mamluk and Ottoman eras saw the formation of a complete architectural identity. Bathhouses became standalone structures funded by waqf (endowment) systems.

In Istanbul alone, by the end end of the 16th century, records of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent documented over 400 operational bathhouses.

According to a study published by the UNESCO Mediterranean Heritage Project, Damascus alone had over 300 traditional bathhouses in the early 20th century, but today fewer than 20 remain.

Traditional bathhouses were not merely buildings for hygiene; they were spaces for reshaping social relationships and staging rituals tied to major life events like marriage, childbirth, and pilgrimage.

Social and Cultural Function

Traditional bathhouses were more than just sanitary facilities; they were social institutions—spaces for meeting, exchanging news, and celebrating rituals. They were mandatory before religious and social events and served as indirect commercial hubs, surrounded by barbershops, perfumeries, and other trades. In some cities, specific times were allocated for men and women, and some bathhouses were gender-specific.

Certain bathhouses offered special services like “bridal baths” or “postnatal baths,” accompanied by traditional rituals, songs, and dedicated attire, as documented in Ottoman and 18th-century Damascene manuscripts.

Decline of Bathhouses – Causes and Consequences

Despite their architectural and social value, many traditional bathhouses in the Eastern Mediterranean have been neglected or collapsed due to:

Changing Lifestyles: The rise of home plumbing systems eliminated the need for public baths.

Architectural Modernization: Preference for modern buildings over heritage structures for economic reasons.

Weak Waqf Maintenance: Privatization policies or administrative neglect reduced the role of endowments in funding maintenance.

According to the ICOMOS Middle East 2022 report, over 70% of historic bathhouses in Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine are at risk of disappearing or have been decommissioned without effective preservation or rehabilitation plans.

The Loss Is Greater Than a Building

When a traditional bathhouse collapses, we lose:

Architectural Heritage: These structures are not just buildings but architectural laboratories where centuries of experimentation in thermal engineering, water management, and functional spatial organization took place.

Cultural Memory: Bathhouses were spaces for celebration, social life, and rare gathering places for women. They were tied to marriage, birth, pilgrimage, and festivals, inspiring folk literature, music, and special attire.

Economic and Industrial Loss: Abandoned bathhouses deprive us of cultural tourism opportunities. Reviving them creates local jobs in restoration, maintenance, and service.

Sustainability School: Bathhouse architecture embodies principles of energy efficiency, water management, and natural insulation.

Urban Social Fabric: Bathhouses were part of an integrated network with markets, mosques, and schools. Their loss dismantles a vital “living nerve” of the old city.

Traditional Crafts: From dome maintenance to decorative arts, these crafts are at risk of extinction.

The UNESCO & ICCROM 2023 report indicates that restoring 100 historic bathhouses in Turkey, Morocco, and Syria could create over 1,200 permanent jobs and increase tourism revenue by 15% in old neighborhoods.

In Tripoli, Lebanon, over 12 traditional bathhouses operated until the early 20th century. Today, only three remain operational, with the rest converted into warehouses or abandoned, despite the city being the second-largest Mamluk architectural complex after Cairo.

Can Bathhouses Be Revived in Contemporary Architecture?

Some countries have already begun reviving traditional bathhouses with a modern vision:

• Morocco: Bathhouses rehabilitated as health spas and cultural tourism centers.

• Turkey: Some restored bathhouses are integrated into luxury historic hotels.

• Tunisia and Syria: Local initiatives to reactivate bathhouses lack financial and administrative support.

The call is not to turn every historic bathhouse into a resort but to integrate this architecture into urban rehabilitation projects, preserving authenticity and restoring its social function.

Ideas for Reviving Traditional Bathhouses Without Compromising Authenticity:

Cultural Rehabilitation: Transform bathhouses into interactive museums showcasing traditional bathing rituals, with audio-visual displays, cultural workshops, or limited artistic performances (traditional music, storytelling) that respect the space’s aquatic and contemplative nature.

Responsible Tourism Investment: Reopen bathhouses as “traditional tourist baths” with strict systems to prevent deterioration of original elements. Offer guided augmented reality (AR) tours showing how the bathhouse operated in different eras. Add a small café or library nearby for economic sustainability without distorting the original use.

Urban Integration: Link bathhouses to a Cultural Trail including old mosques, markets, and schools, with signage and urban design guidance. Incorporate them into modern wellness tourism while preserving traditional heating, massage, and natural treatments.

Authentic Materials and Restoration Techniques: Preserve traditional heating systems (hypocaust) with discreet modern upgrades. Restore domes and decorations using traditional plaster and tile techniques under skilled craftsmen, with scientific documentation. Apply preventive conservation to control humidity and prevent decay.

Functional and Urban Integration: Establish a “Traditional Architecture Study and Training Center” adjacent to the bathhouse to train specialists in rehabilitation. Design housing or urban services inspired by its architecture, making it the core of sustainable urban design respecting local spaces and climate.

Ideas in this field are abundant and worthy of study, such as transforming a traditional bathhouse into a natural therapy center supported by educational tours, or developing an adjacent outdoor space as a heritage café offering local cuisine, ensuring sustainable income for maintenance. Another example could be converting a historic bathhouse into an exhibition space on water architecture in Islamic cities, with an educational activity hall… all as illustrative examples.

Notable Architectural Cases

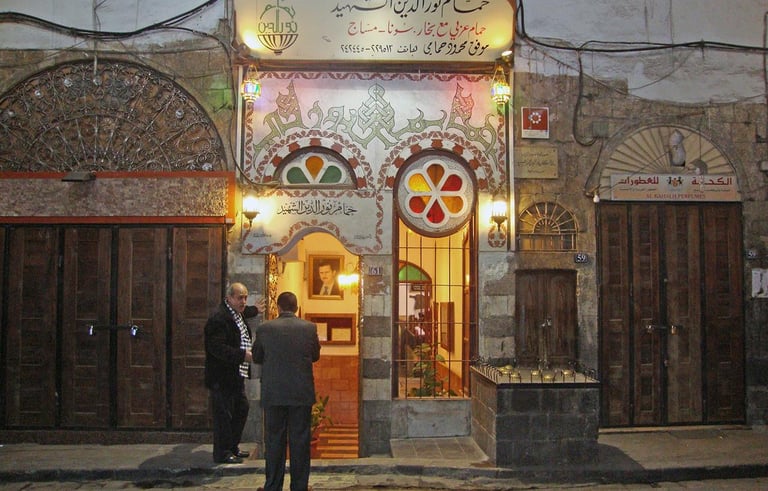

Nur al-Din Bathhouse – Damascus

Renovated in the 12th century by Prince Nur al-Din Zangi, it symbolizes Damascus’s prosperity after a critical period. Visitors transition from a 6.5-meter-high entrance (barrāni) to the jawwāni, where a perforated dome covered in stained glass allows soft light and vertical steam flow, preventing condensation. Local materials like limestone, plaster, and marble are used for seating.

Still a destination for visitors to Old Damascus, especially as it’s located within historic markets, Nur al-Din Bathhouse remains famous for its original structure and continues to offer traditional public bathing services.

Sultan Hürrem’s Bathhouse (1556 CE) – Istanbul

Designed by the renowned architect Sinan Pasha, this bathhouse features a unique double hamam design: two identical yet completely separate sections for men and women, with separate entrances. This innovative layout provided maximum privacy and was ahead of its time. Its dual air and water heating system, with precise steam distribution, reduces heat loss by 40% compared to modern techniques, according to a 2021 study in The Journal of Islamic Environmental Studies.

After recent restoration, it has become more than a public bath—a tourist landmark in itself. Its prime location between Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque makes it a key stop for visitors to the historic area. It blends rich history with modern luxury, offering an authentic Turkish bath experience in the heart of Istanbul.

Share the post

Subscribe to our newsletters:

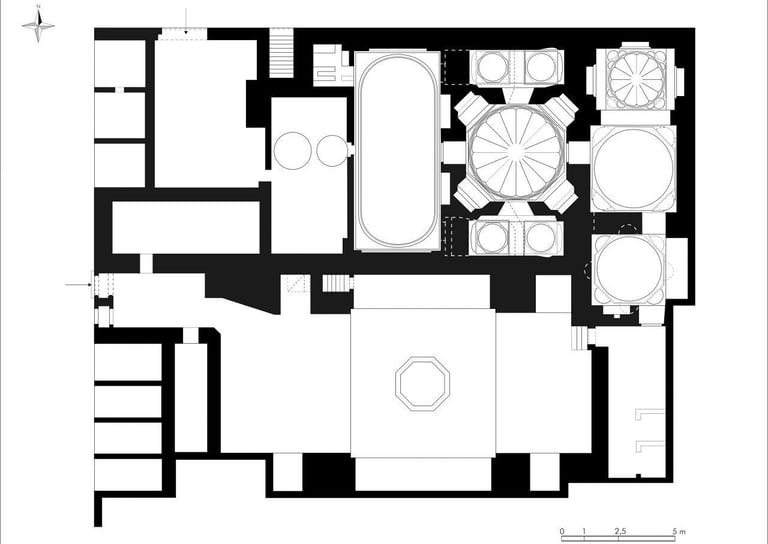

The Architectural System – Spaces and Their Functions

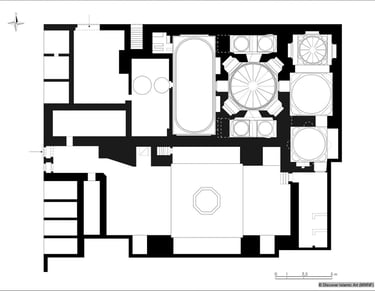

Traditional bathhouses were designed according to a psychological, thermal, and social sequence. Their architectural genius lies in the intelligently organized thermal gradient, typically consisting of three main sections, each with specific spaces and functions:

Al-Barrāni (Cold Section):

Begins with the entrance, including the changing room (mustrāḥ) and a spacious hall for reception, changing, and relaxation. Often covered by a dome, it features a central fountain. This space allows visitors to gradually transition from the outdoor climate to the bathhouse’s internal atmosphere. It includes storage and service areas.

Al-Wustāni (Warm Section):

A moderate thermal transition prepares the body for the jawwāni (hot section). It may be used for relaxation or steam preparation, with adjacent spaces for post-bath services like massage and rest.

Al-Jawwāni (Hot Section):

The heart of the bathhouse, with dense steam, bathing cubicles, water basins (jurn), and carefully designed hot water and steam systems. Thick walls retain heat, and water is heated via channels.

Adjacent service spaces include:

• Bayt al-Nār (Furnace): The heat source, located underground or in a rear isolated space.

• Water Tanks and Boilers: For distributing cold and hot water.

• Fuel and Supply Storages.

• Separate entrances and services for staff.

This arrangement ensures thermal comfort and minimizes the shock of transitioning between temperatures, reflecting a deep understanding of human physiology.

Construction Techniques and Materials

Traditional bathhouses were an advanced example of sustainable environmental architecture, even before these modern terms were used. Ancient architects considered the balance between heat, humidity, ventilation, and light distribution, achieving this with highly efficient local materials and techniques.

Bathhouses in the Eastern Mediterranean were not built randomly but combined architectural, aesthetic, and environmental functions. Key materials and techniques included:

Local Stone (limestone, basalt, sandstone): Used for walls and ceilings. Thick stone walls provided thermal insulation, and local materials reduced construction costs while ensuring visual integration with the surrounding urban fabric.

Marble and Qashani: For surfaces, floors, basins, and benches. Marble retains heat, resists moisture, and is easy to clean. White marble symbolized purity, while colored qashani was added later in Ottoman bathhouses.

Plaster, Lime, and Gypsum: Used for domes, arches, moisture insulation, and decorative touches. Plaster decorations also regulated light and sound within the bathhouse.

Tiles: Often used for domes and curved roofs due to their lightness and durability.

In rural and smaller areas, bathhouses were typically built from local stone or mud, without decorations, serving entire villages. They were often adjacent to mosques or local schools. In major cities, however, bathhouses became large architectural institutions, linked to urban blocks, funded by endowments, and featuring intricate decorations and advanced heating systems.

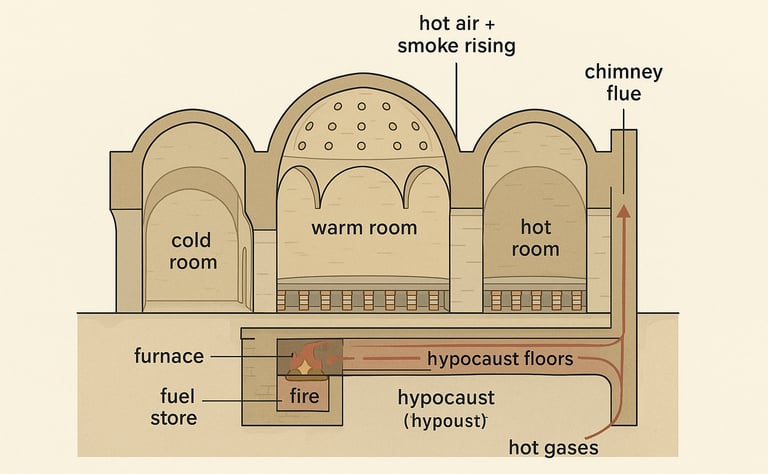

The Hypocaust System: Thermal Genius Before the Age of Technology

The Hypocaust system, a Roman invention later adopted and ingeniously modified by Muslims for traditional bathhouses, is a testament to pre-technological thermal engineering. The term derives from Greek: hypo (under) and caust (combustion), literally meaning "burning from below."

The heating system consists of interconnected elements working together to distribute heat:

Furnace (Hypocaust Furnace):

Typically located outside the bathhouse or in an isolated section to prevent smoke accumulation. Fuel (wood or coal) is burned to heat water and air. The furnace is designed to regulate heat flow, with openings for fuel input and exhaust gases.

Underfloor Heating System (Hypocaust System):

The core of the heating system. A network of air channels (60–80 cm high) is created beneath the raised floors, supported by small pillars (pilae) or arches. Hot gases from the furnace flow through these channels, heating the floor tiles, which radiate warmth into the rooms above.

Wall Flues (Tubuli):

Vertical clay pipes or channels embedded in walls between rooms or externally. After passing through the underfloor system, warm gases rise through these flues, providing additional wall heating, preventing condensation, and ensuring continuous airflow. They connect to a main chimney for exhaust.

Floors, Walls, and Ceilings:

Built from high thermal mass materials like stone, brick, or lime concrete. These materials absorb heat slowly, retain it, and release it gradually, acting as radiant surfaces that warm both air and occupants.

Why Is This System an Architectural Marvel?

It achieves localized heating without energy waste, using local materials (stone, clay, marble) to store and regulate heat, humidity, and ventilation. This system is a precursor to modern Central Heating Systems and is classified as Passive Architecture, relying on natural elements without external energy consumption.

The Hypocaust System Relies on Key Thermal Principles:

Convection:

Hot gases rise from the furnace into the underfloor channels and wall flues due to their lower density, creating a continuous flow that distributes heat and warms room air.

Conduction:

Heat transfers from hot gases to floor layers, walls, and clay flues via direct contact.

Radiation:

Once floors, walls, and ceilings are heated, they emit infrared radiation, directly warming occupants—a key factor in the "comfortable warmth" experienced in bathhouses, as bodies are heated more than the surrounding air.

Controlled Thermal Gradient:

Bathhouses are designed with a thermal sequence: cold (Frigidarium), warm (Tepidarium), and hot (Caldarium) rooms. Hot gases first heat the Caldarium, then flow to the Tepidarium, and finally to the Frigidarium or main chimney, maximizing energy use. Wall thickness and materials vary between rooms to control heat transfer.

This system is classified as a "Passive Architecture" technique, which relies on investing in elements Nature without consuming external energy.

Perforated Domes (Qamariyyat System):

Small circular openings in domes, called Qamariyyat, are both functional and artistic. They allow hot air to rise in the jawwāni, expelling steam vertically without condensing on users. Covered with translucent glass or ceramic, they provide controlled natural light without heat loss—an early example of Passive Lighting and Ventilation.

Subscribe to our newsletters:

Finally:

Allowing traditional bathhouses to become distorted or abandoned is a real danger… There is a genuine opportunity to restore their role, history, and identity.

These structures are not just adjacent luxuries but human architectural imprints that speak through heat, steam, and social rituals. How many stories of neighbors, encounters, and lost traditions are hidden within their towers and domes? We must see them as prototypes for the sustainable design adopted by future cities, because they truly are.

The deeper we delve into them, the better we understand the true architectural identity of our cities… and how they can shape our desired architecture.

Traditional bathhouses are not just beautiful relics for viewing but integrated architectural and human models that can inspire sustainable future construction and urban communities, opening significant cultural, tourism, and economic horizons.

Reviving these bathhouses requires more than restoring their stones; it demands a deep understanding of their functional, cultural, and architectural essence, and recognition that they are part of the architectural identity of the Eastern Mediterranean.